Sena Akça

Migration Studies Online Internship Program

Abstract

Migration is a complex process shaped by economic, social, cultural, and political factors. However, the reasons why people do not migrate are equally important. This study explores the reasons behind people’s decision not to migrate, focusing on the concepts of voluntary and involuntary immobility. Factors like economic limitations, social ties, cultural adaptation issues, and political restrictions play a role in the decision to stay. I examined these factors and their impact on individuals’ decision to remain in their current location through migration theories.

Keywords: migration theories, non-migration, involuntary immobility, migration processes

Introduction

Migration is often linked to economic and social mobility in the literature. If they people have economic stability and social acceptance they don’t chose to migrate. However, the decision not to migrate is just as significant, and the reasons behind this choice are complex. People may avoid migrating due to economic, social, cultural, and political reasons. This paper focuses on why people choose not to migrate, offering an analysis through the concepts of voluntary and involuntary immobility. Studies on involuntary immobility, this term explains sometimes individuals cannot migrate for various reasons even though they have the opportunity, and sometimes although they don’t have enough facility, there are many pushing factors that require them to migrate are limited in the literature, but this phenomenon deeply affects people and will likely become a subject of more research in the future. The goal of this study is to examine in detail the conscious and unconscious factors that influence individuals’ decisions to stay in their current locations.

Migration Theories

Migration happens for many reasons, and theories help us understand why people move. By examining the motivations and conditions that drive migration, we can also better comprehend why some individuals choose, or are forced, to stay in their current locations. Migration theories offer a useful contrast, illustrating how certain economic, social, or cultural factors that encourage movement might also create barriers that lead to involuntary immobility. This concept refers to individuals who may wish to migrate but are unable to do so due to constraints like financial limitations, social ties, or political restrictions. Even when migration is possible, some may choose to stay due to strong attachments to their home, fear of change, or lack of access to the networks that facilitate migration for others. Thus, understanding both the factors that drive migration and those that prevent it provides a more complete picture of why some people remain immobile despite the forces that encourage mobility. To fully grasp immobility, it is crucial to first understand the conditions that lead to and sustain mobility.

Wallerstein’s World-Systems Theory (Wallerstein, 1989) looks at migration through the lens of the global economy. It divides the world into core (rich) and periphery (poor) regions. People move from poorer areas to richer ones because richer areas need labor, and poorer areas have people looking for better opportunities. An example is the migration of workers from Turkiye to Germany after World War II. Germany needed workers to rebuild its economy, and Turkish workers were looking for better jobs.

Migration Systems Theory suggests that once migration starts, it often becomes a larger, ongoing process. People who migrate build connections between their home country and the new country, making it easier for others to follow. Over time, what begins with a few people moving can turn into a large-scale migration. (Faist,2000, p.190)

According to the Neoclassical Economic Perspective, the main reason for migration is economic. This theory says that people move to places where they can earn more money and have a better life. Migration will continue until the differences in income and living conditions between countries become smaller. (Adıguzel, 2020, p.30)

Finally, Lee’s Push-Pull Theory (Lee,1966) explains that people decide to migrate due to two main reasons: push factors and pull factors. Push factors are the problems in their home country, like unemployment or war, that make them want to leave. Pull factors are the good things in another country, like job opportunities and safety, that attract them. (Suna&Cereci, 2022, p.198)

While migration theories provide us with a deep understanding of why people move, examining immobility under a different heading allows us to clarify the factors that shape individuals’ ideas about migration. Understanding immobility requires a different perspective, focusing on the constraints and barriers—both voluntary and involuntary—that prevent migration. By addressing immobility theories, we can gain insight into the complex reasons why some individuals are unable or unwilling to move, ultimately offering a more complete view of human mobility and decision-making.

Immobility Theories

There are theories of migration as well as theories of immobility. Migration decisions are not only shaped by the desire to move but also by the choice to stay. Immobility, or the decision not to migrate, can result from both conscious and subconscious calculations made by individuals. When people feel secure, have acces to basic needs, and are socially well placed, they are less likely to seek migration. According to the theory of “the value of immobility”, staying in one place can offer many advantages.

For instance, in institution-specific value, individuals become familiar with the methods, processes, and culture of their workplace, making it more beneficial to stay.

Similarly, in location-specific value, speaking the local language, understanding the political and legal environment, and having social capital like networks and acquaintances provide long-term benefits that influence the decision not to migrate.

On the other hand, the presence of familiar people in a destination country plays an important role in migration decisions, the first-generation migrants, through their community organizations, often help second-generation migrants with housing, transportation, and job finding. A lack of such support can discourage migration who failed to integrate into the new society may further affect the migration decision. (Suna&Cereci, 2022, p.198)

Wolpert’s Stress-Threshold Model (Wolpert, 1965) suggests that factors like economic conditions, job opportunities, social networks and security influence migration decisions. When these conditions worsen, they raise individuals’ stress levels, prompting migration. However, every person has a different stress threshold, which means their reasons for migration vary widely.

For example, the Uyghur people in East Turkistan are experiencing severe oppression under China’s assimilation policies. Despite having valid reasons to migrate, they are restricted from leaving due to political barriers. Many Uyghurs, even when they seek asylum, are denied or delayed in their requests, leading to continued suffering despite the high levels of stress that would typically drive migration decisions. (Carrdus, 2023)

Reasons for Non-Migration: Social, Economic and Cultural Context

Migration presents both risks and opportunities. It requiers certain financial resources, making it a risky decision for those without financial security. People may postpone their migration plans due to the fear of losing their property or financial safety.

In addition, concerns about adapting to the cultural environment of the decision to stay. Many individuals delay migration due to fears of not fitting into the new culture. Women, in particular, often face psychological challenges when they are forced to migrate due to their family roles social isolation and language barriers are common issues that make the migration process harder for women. According to a study on the impact of migration on womens’s mental health, many women struggle with these challenges. (Tuzcu& Ilgaz,2023, p.57-67)

Although the number of women in high-status, well-paying jobs has increased over the years, this situation is not universal. Similarly, differences between the religion, politics and culture of the source and destination countries are also important factors influencing migration decisions. In France, for example many women are excluded from education because they wear headscarves, (Al Jazeera, French to ban wearing headscarves and abayas dress in school, 27 aug 2023) a situation that has also occurred in Turkey. (Al jazeera Turkiye, headscarf ban in Turkiye, how it started/ how it ended? 30 Dec 2013)

Therefore, individuals who already face discrimination in their home country may hesitate to migrate, fearing even worse treatment abroad.

Similarly, Suna and Cereci’s fields studies in Turkey gathered the following perspective from a woman who faced this dilemma:

Woman (30): “My husband is very interested in migrating. A close friend of ours moved to the UK under the Ankara Agreement. I have never liked the idea of migrating because of my social concerns. As a woman wearing a headscarf, I even worry if I will be judged when I go to the beach during summer holidays. If I feel this way in my own country, I can’t imagine going to another country. Beyond my headscarf, I don’t think I deserve the discrimination and humiliation that migrants face.” (Suna&Cereci, 2022, p.202)

On the other hand, children and young migrants may also struggle to adapt to new environments. Language and culture are crucial elements that connect people to their surroundings. In schools where the curriculum is taught in a different language or culture, children may have difficulty adapting and face challenges in continuing their education. This makes it harder for them to move up to the next level of education.

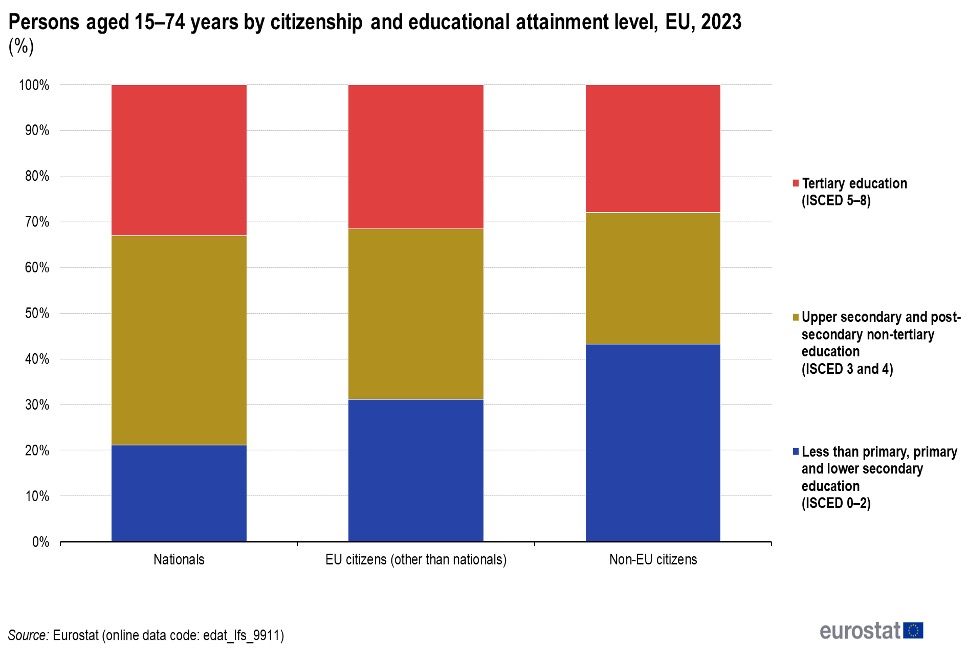

The following table presents an analysis of the differences in educational continuation and levels between citizens and non-citizens in European countries.

The Dynamics Between Migration and Immobility

While the concept of migration has been extensively studied in the literature, the concept of non-migration has not received the same attention. Just as migration is a societal process, so is staying in place, and it deserves an in-depth analysis. In fact, non-migration offers a perspective of solution for many researchers who see migration as a problem. However, staying in place can become a serious issue in the face of challenging conditions such as war, persecution and famine. Out of the 7.8 billion people in the world, only 272 million are international migrants. Some migrate for economic reasons, such as to meet their basic needs, while others migrate to escape political and social oppression or simply to seek a better quality of life. However, billions of people choose not to migrate and remain where they are. (Esipova et al, 2018.)

So, why don’t more poeple migrate, even when there are life-threatening reasons to do so?

This dynamic can be explained by the “desire and capacity model”. Even if people desire to migrate, they may lack the necessary resources or the capacity to make it happen. Migration requiers not just a willingness to leave but also financial, social and sometimes physical resources. Additionally, strong cultural ties, fear of the unknown and social pressures may further inhibit migration decisions even in situations where it might seem necessary. The desire to migrate or stay in place is distinct from the ability to do so. This distinction leads to three different types of immobility: resigned (accepting), voluntary and involuntary immobility. (Carling et al., no. 6 (2018): 945–63.)

Involuntary immobility

This term was first introduced by Jorgen Carling. It refers to individuals who wish to migrate but are prevented by factors such as restrictive immigration policies. Carling also emphasized that large migration flows are often linked to involuntary immobility. For example, in Mozambique, labor migration played a vital role in the social and economic life of drought-prone areas. However, when the civil war broke out, this movement stopped, and the most disadvantaged groups were tapped in their villages due to the conflict. These populations, referred to as “displaced in place” are often invisible in the migration and refugee fields. In addition to those unable to leave their homeland. Joris Schapendonk highlighted that many irregular migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, who aimed to reach Europe, became stuck a result, these migrants experience a form of immobility while in movement. Similarly, refugees who have been forced to flee their countries may remain confined to camps for decades or even generations. Jennifer handmade and Winona Giles argued that long-term refugee situations have become the new normal. “For refugees, waiting is not the exception, but the rule.” Refugees who dare to escape forced uncertainty and seek a new life elsewhere are often seen as security threats. Hyndman and Giles put it: “The good refugee is the one who waits in place.” (Lubkemann&Stephen C., 2008, p.454-75)

Migration and Staying Capacity

In the future, migration is expected to become voluntary rather than involuntary. The capacity to stay is seen as developmental goal, providing people the freedom to achieve well-being in their current location. According to the Capability Approach theory, development should be assessed based on people’s ability to become what they value and have reason to value. From this perspective, exploring the capacity to stay means examining whether individuals have realistic options to achieve their life goals where they are. (De Haas, Hein, 2021)

Focusing solely on the ability to migrate overshadows the significance of staying capacity. While the desire to stay or migrate is important, staying capacity is not the opposite of migration ability. Migration ability refers to the resources -financial, social and human- required for someone to move from one place to another. In contrast, staying capacity refers to having the opportunities and resources to fulfill one’s aspirations in their current location.

It is not simply about remaining stationary; those who cannot realize their goals where they are lack the capacity to stay.

Calls for people to stay in place have been criticized for indirectly supporting migration regimes that restrict freedom of movement. Former UN High Commisioner for Refugees, Sadako Ogata, argued in 1993 that those affected by crises should have the “rigt to stay” indirectly challenging policies that limit asylum rights. (Hyndman&Jennifer, 2003, p.167–85)

Focusing on staying often leads to measures that restrict freedom rather than enhance well-being. Enhancing staying capacity does not mean reducing migration. Hein de Hass, describes human mobility not simply as the act of moving but as the ability to choose where to live, including the option to stay. From a normative perspective, while many may still choose to migrate, all people should have the capacity to stay if they wish. (Schewel& Kerilyn, 2015)

Policy and Immobility

Policies are one of the critical factors directly influencing individuals’ migration decisions. Their is a wide range of forced and voluntary immobility. Recognizing the different types of immobility can increase the effectiveness of policies.

For example, as research on the efffects of the COVID-19 pandemic grows, it is becoming clear that while the pandemic has increased the need for economic migration among many low-wage workers, public health restrictions have simultaneously limited their ability to migrate. Finding ways to mitigate involuntary immobility is crucial to restoring livelihoods for affected populations. Similarly, it is essential to recognize that in crisis situations, those trapped by conflicts or disasters are often among the most vulnerable. Humanitarian efforts must continue to focus on how best to reach populations that are immobile and how to reduce the likelihood of involuntary immobility in crises. (Mixed Migration Centre, “Impact of the COVID-19 on the Decision to Migrate.”2020.)

Findings of Fieldwork

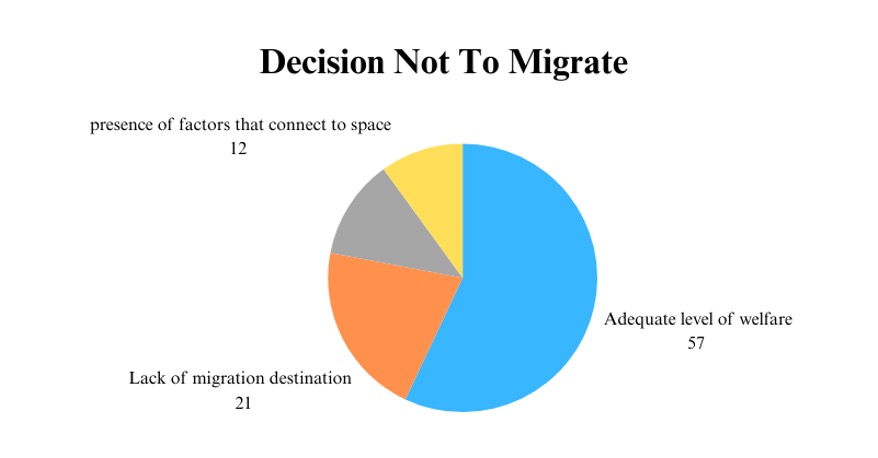

The field views in this study were taken from Anıl Suna and Sedat Cereci’s research on the reasons to theoretical framework is supported by fieldwork conducted in several provinces of Turkiye, including Gaziantep, Van, Diyarbakır, Batman, Artvin, Rize, Giresun, Balıkesir, Adana and Hatay. In this research, 100 participants were interviewed and the findings revealed diverse reasons for migration or staying. (Suna&Cereci, 2022, p.203)

- 57% of participants stated that they did not consider migration because they were satisfied with their current situation.

- 21% of participants expressed that, although they felt the need to migrate, they could not do so due to factors such as lack of direction or financial constraints.

- 12% of participantsreported that they chose not to migrate due to a strong connection to their homeland, citing reasons such as maintaining their established way of life or patriotism.

- 10 % of participants giving the answer of I don’t know

These findings highlight how personal satisfaction financial barriers and attachment to one’s homeland can shape individuals’ decisions to migrate or stay.

Table translated by the author from Turkish to English (Suna&Cereci,2022, p. 203).

Conclusion

This study set out to investigate the complex reasons why individuals choose not to migrate, focusing on the interplay of voluntary and involuntary immobility. The decision not to migrate is shaped by a range of economic, social, cultural, and political factors, with voluntary immobility reflecting contentment with current living conditions, while involuntary immobility highlights the barriers that prevent individuals from moving, even when they wish to. Despite the desire to migrate, factors such as financial limitations, social obligations, and political restrictions can constrain mobility, illustrating the multi-dimensionality of immobility.

However, a lack of fieldwork, particularly in the area of involuntary immobility, has limited our deeper understanding of this issue. Field studies that explore the psychological and sociological dynamics underlying non-migration could address these gaps and offer more insight into why some individuals remain immobile despite facing considerable push factors.

Future research should address this phenomenon more comprehensively, as it will help us better understand migration movements and the challenges people face when migration is not a viable option. The findings presented in this paper emphasize that understanding why people do not migrate requires consideration of economic, social, cultural, and psychological perspectives together. Expanding research on involuntary immobility, through fieldwork and theoretical exploration, would contribute significantly to a more complete understanding of this critical area in migration studies.

References

- Suna, A. and Cereci, S. (2022). ANATOMY OF NON-MIGRATION IN THE CONTEXT OF MIGRATION THEORIES. Hatay Mustafa Kemal University Journal of Social Sciences Institute, 19(49), 195-208.

- Giordano, C. ve Boscoboinik, A. (2018). Society: A Key Concept in Anthropology. Ethnology, Ethnography and Cultural Anthropology, Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), Ed. Paolo Barbaro, Abu Dhabi, U.A.E: UNESCO, Eolss Publishers, s. 2-13

- Uyghur Human Rights Project, failure to protect Uyghur refugees, Uyghur experiences with UNHCR, June 2023 https://uhrp.org/report/i-escaped-but-not-to-freedom-failure-to-protect-uyghur-refugees/

- The effects of migration on womens’s mental health, Ayla Tuzcu, Ayşegül Ilgaz, journal of current approaches in psychiatry, 57-67 https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/pgy/issue/11143/133479

- French to ban wearing headscarves and abayas dress in school, Al Jazeera, 27 aug 2023 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/8/27/france-to-ban-wearing-abaya-dress-in-schools-minister

- Al jazeera Turkiye, headscarf ban in Turkiye, how it started/ how it ended? 30 dec 2013 https://www.aljazeera.com.tr/dosya/turkiyede-basortusu-yasagi-nasil-basladi-nasil-cozuldu

- Persons aged 15-74 years by migration status and educational attainment level, EU,2023 https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Foreign-born_people_and_their_descendants_-_educational_attainment_level_and_skills_in_host_country_language

- Esipova, Neli, Anita Pugliese, and Julie Ray. “More Than 750 Million Worldwide Would Migrate If They Could.”Gallup World Polls, December 10, 2018.

- Carling, Jørgen, and Kerilyn Schewel. “Revisiting Aspiration and Ability in International Migration.”Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44, no. 6 (2018): 945–63.

- Hyndman, Jennifer. “Preventative, Palliative, or Punitive? Safe Spaces in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Somalia, and Sri Lanka.”Journal of Refugee Studies 16, no. 2 (2003): 167–85.

- Lubkemann, Stephen C. “Involuntary Immobility: On a Theoretical Invisibility in Forced Migration Studies.” Journal of Refugee Studies21, no. 4 (2008): 454–75. https://academic.oup.com/jrs/article-abstract/21/4/454/1583335

- Schewel, Kerilyn. “Understanding the Aspiration to Stay: A Case Study of Young Adults in Senegal.” International Migration Institute, January 2015. https://www.migrationinstitute.org/publications/wp-107-15

- Mixed Migration Centre. “Impact of the COVID-19 on the Decision to Migrate.” December 10, 2020. https://mixedmigration.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/154_covid_thematic_update_drivers_and_outlook.pdf