Abstract

The aim of this article is to portray the relation between active civil society and the process of democratization. Therefore, providing the operational definitions for democracy and civil society is one of the concerns of this article yet not the only. Although from the theoretical perspective as well discussed, democracy and civil society might seem positively correlated, hand in hand. On the other hand, active civil society engagement does not always facilitate democratic actions nor bring democracy. To the point of which, the aim of this article is evaluating the democratic or non-democratic processes in Turkey, based on the Copenhagen Criteria, and also to compare Turkey’s position with other EU members. Following that, the democratic processes so far evaluated are reconsidered in the aim of demonstrating the impact of civil engagement and civil action and civil society practices.

Keywords: democratization, civil action, European Union, Turkey, civil engagement

Introduction

This article cultivates on the question that “how is the alignment between civil society’s activity and the democratization of legal and political phases run by the government?” The word “democratization” is always used together with European Union, especially after Turkey’s accession started to be reconsidered since 2005, when the negotiations for official membership started (European Commission, 2006). After this date, negotiations are opened and closed for several times, because of several disagreements, such as Cyprus dispute and suspended completely after the 2016 “refugee deal” made between Turkey and European Union. Although it is expected from the deal to accelerate the negotiations, another reason for the suspension of the negotiations for official membership of Turkey, is the fallacies and malfunctional practices against the “Copenhagen Criteria” (Candar, 2017). The criteria require that a state has the institutions to preserve democratic governance and human rights, has a functioning market economy, and accepts the obligations and the EU’s intent.

In the following, the first section Democracy in Turkey: An evaluation based on Copenhagen Criteria aims to scrutinize how democracy is measured, what are the criterion for democratic governance and how it is operationalized by the European Union. After the practices in Turkey are evaluated under the scope of Copenhagen Criteria, the individual evaluation of European Union members in terms of democratic practices, sustainable governance and rule of law will be discussed at the end of this chapter. In the second and the last chapter along with the conclusion, the democratic processes so far evaluated are reconsidered in the aim of demonstrating the impact of civil engagement and civil action and civil society practices.

Democracy in Turkey: An evaluation based on Copenhagen Criteria

“Democracy is a political ideal that principally applies to arrangements for the making of binding collective decisions. Such arrangements are democratic if they ensure that any authorization to exercise public power arises from collective decisions by the citizens over whom that power is exercised.”

As it is stated in the book of Steffek, Kissling, and Nanz, published in 2008 under the name of Civil Society Participation in European and Global Governance: A Cure for the Democratic Deficit?, policy making and government are for and coming from the demos, and the power is allocated to the demos as well, only if the rule of government is protecting the collective decisions that bind the people within the related territory. Based on this definition and the following interpretation, demos including every citizen should have the rights to participate in policy making processes, local and general elections. It is also noteworthy to add to the point of which each vote of the member of the demos has equal contribution to the overall voting meaning that all votes should be counted as equal (Dahl, 2020).

Necessary rights should be given and sustained to the demos by the government for demos to provide free participation to a fair and just election/policy making decision. These rights are in general will be mentioned as “fundamental rights”:

- Right to access uncensored information

- Right to freely express thought and ideas

- Freedom for media and press

- Right to vote

- Right to directly participate to the policymaking

After portraying the desideratum of democracy as it is declared by the European Union and confirmed by all of its members, the evaluation of the practices held in Turkey will now be discussed.

Based on Sustainable Governance Indicators (2020), the quality of the democracy has dropped by 1.4 points compared to its 2014 level and now ranked last from the 41 European countries. This decrease can be explained by the recent coop intervention held in 2016 and transitioning to a new executive system, whose name is the Presidential Government System in Turkey. This system allows the president to participate in the practices of both legislation and execution of the constitutional law. Therefore, the authorities of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey are restricted. It also comes with this new executive system that the President might hold a position in a political party. All these circumstances considered Turkey scores 4.3 points below the Average of European Members with a score of 2.9 out of ten. Same score applies to the criteria of Rule of Law (Stiftung, 2020). Same indicators evaluated the criteria of Media Access in Turkey with a score of two out of ten, with proposing the rationale behind as substantial censorship in media and media pluralism meaning the sources and the index of the information published has been controlled and realigned with the perspective of the government. It can also be provided as evidence that many journalists and column writers, editors, academicians and many credible others are detained and their positions are suspended because they used their right of freedom of speech yet, their claims were against the agenda of the president. It can also be added that, government does not follow the principles of transparency and responsibility to the demos. These facts can also be supported by the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index (2020), portraying global rank constitutes of 128 countries and in which Turkey ranked as bottom 5th for the criteria of Constraints on governmental powers and bottom 6th for sustaining fundamental rights.

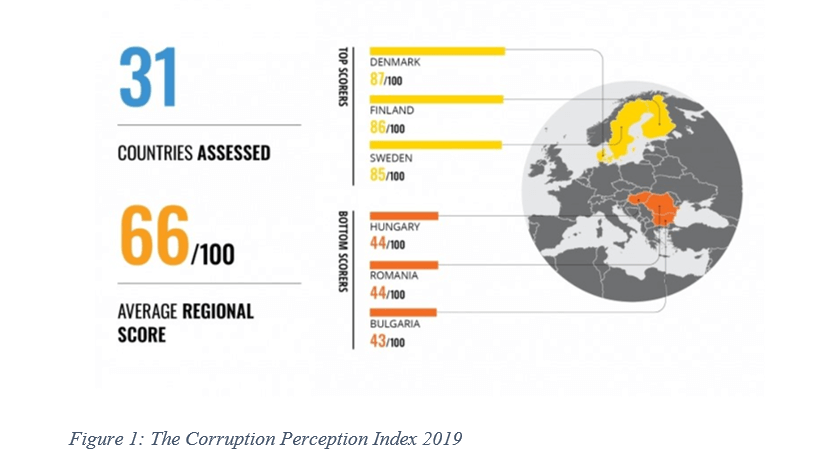

While so far, Turkey is compared either globally or with the average of EU members, it is interesting to investigate the EU members individually in which democratic practices are not followed homogeneously throughout the union. While north European countries are the example of transparent and responsible democracy empowering the decisions of demos and rule of law, the north/south of the Europe countries as Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania are suffering from limitation of freedom of speech and other fundamental rights, individual profit based decisions over the population profit, corruption and bribery.

The Impact Of Civil Engagement And Civil Action On Democratization Processes

Civil society can be described as many. Most well-known definitions including the definitions of United Nations (2019), World Economic Forum (Jezard, 2018) describes the civil society as a third sector, a public domain between the private sector and government, including the institution of family and non-governmental institutions. Since this study holds more pragmatic approach rather than descriptive, the preferred description of civil society provided by the London School of Economics Centre for Civil Society (2004):

“Civil society refers to the arena of uncoerced collective action around shared interests, purposes and values. In theory, its institutional forms are distinct from those of the state, family and market, though in practice, the boundaries between state, civil society, family and market are often complex, blurred and negotiated. Civil society commonly embraces a diversity of spaces, actors and institutional forms, varying in their degree of formality, autonomy and power. Civil societies are often populated by organizations such as registered charities, development non-governmental organizations, community groups, women’s organizations, faith-based organizations, professional associations, trade unions, self-help groups, social movements, business associations, coalitions and advocacy groups”.

For some of its advocates, the achievement of an independent civil society is a necessary precondition for a healthy democracy, and its relative absence or decline is often cited as both a cause and an effect of various contemporary socio-political maladies. (Kenny, 2016). To elaborate on this, the characteristics of the notion of civil society like being apart from governmental organization, nourishing from voluntary action and participation, being transparent, accountable and working both for and with the public is also quite fundamental for a fulfilling democracy. From this perspective, theoretically speaking, the more civil communities grow, the better and the bigger presence of civil society may be in governmental institutions. This acknowledgement and the large amount and numbers of civil action will result in government-centered policy-making to fade and public-centered policy making to rise. Therefore, the activity of civil society predisposes the policies securing the well-being and inclusion of demos and the demos literally play an active role in imposing the need for these policies to the government thus play an active role in decision-making practices.

In this point it is critically important to remind the importance of fundamental rights and especially freedom of media, to the point of which enables the connectedness and collective cooperation but also demands quick responses for the accountability of actions of the politicians and accelerates the speed of responses coming from public willpower against policies and actions taken by government. In 2013, “The Gezi Occupation” is one of the most astonishing civil actions of the last decade of Turkey, gathered against a government-based decision and resulted in for public good. The social media platform twitter, is the most used medium for this collective action and the related research point out that tweets including “#direngeziparki” (i.e. resist Gezi Park) used almost for two and a half million times, and #occupygezi tweets was shared more than three and a half million times (Kurt, 2013). For sure not all the tweets shared are against the public policy yet this community them all enabled to foster the information flow and cooperate via social media without being physically present in the field. This is a reaction against irresponsible actions of government and unaccountable policies decided without the notice of the public. Even though the communal action did lead into the change of decided policy, the motivation behind the protests was less of a stand against undemocratic practices. It has been three years that Osman Kavala, Paris born 63 year old Turkish citizen, human rights advocate and philanthropist, is under arrest without any evidence, accused by organizing the Gezi movement and then organizing the coop intervention (which was in 2017). Unfortunately, neither the civil action for Gezi did bring any freedom, transparency or accountability, nor foster any democratization in the juridical practices.

Conclusion

To conclude the main argument of this article is vibrant civil action and active civil society may not always bring democratization. This is especially the case for third-word countries which have economic dependency on other countries, and foreign-funded non-governmental organizations. Another reason for such situation is described by Şerif Mardin (1995) with a more sociological approach that is, the countries in which the Islam is the predominant religion, the demos may perceive the political leader as a savior, a father, an answer for every need, therefore participating to a civil action may not occur as a need for policy change. All the necessary actions should come from the government, and if not, there may not be any need for such policy or action at all. This situation is expressed best with an idiom “her şeyi devletten beklemek” (i.e. expecting all from the state), or “her şeyi devletten bekleme” (i.e. do not expect all from the state).

The last reason that will be posted within the scope in this article is that, by referring to the table shared above, The Corruption Perception Index 2019. In the corrupted governances, in which the accountability and the transparency of governmental practices are in danger, non-governmental organizations and associations may be manipulated against the public good and serve for individual profit. In the beginning of this year, a gas company of Turkish state donate 8 million dollars to Ensar Association, which was known by its rape and sexual assault cases occurred in their dorms (Ordu, 2020). This reasons with the argument that the top political elite is perceived to be the primary beneficiaries of corruption. Thus, while there are valid and noteworthy developments in establishing the legal and constitutional framework to fight corruption via the actions of civil society, there is a continued absence of a clear demonstration of political will to fight corruption (Moyo, 2014).

Elif BAYAT

Sivil Toplum Çalışmaları Staj Programı

References:

Candar, C. (2017). New clashes likely between Turkey, Europe. Retrieved from: https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/06/turkey-european-union-relations-possible-collision.html

Cavatorta, F. (2006). Civil society, Islamism and democratisation: the case of Morocco. Journal of Modern African Studies, 203-222.

Centre for Civil Society, London School of Economics.(2004). What is civil society?

Çildan, C., Ertemiz, M., Tumuçin, H. K., Küçük, E., & Albayrak, D. (2012). Sosyal medyanın politik katılım ve hareketlerdeki rolü. Akademik Bilişim, 3.

Hearn, J. (2010). Foreign aid, democratisation and civil society in Africa: a study of South Africa, Ghana and Uganda. IDS discussion paper series, 368. Brighton: IDS.

European Commission. (2006). “Interview with European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso on BBC Sunday AM” Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 November 2006. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

Jezard, A. (2018). Who and what is ‘civil society?’ Retreived from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/04/what-is-civil-society/

Kenny, M. (2016). Civil Society. Encyclopedia Brittannica Chapter. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/civil-society

Kurt, M. (2013). Gezi direnişinin en popüler hashtagleri: Twitter’da trend topic olan hashtaglerin analizi. Retreived from: https://mediacat.com/gezi-direnisinin-en-populer-hashtagleri/

Mardin, Ş. (1995). ‘Civil society and Islam’, in J. Hall, ed. Civil Society: history, theory, comparison. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Moyo, S. (2014). Corruption in Zimbabwe: an examination of the roles of the state and civil society in combating corruption (Doctoral dissertation, University of Central Lancashire).

Ordu, E. (2020). Başkentgaz Ensar Vakfı’na Kızılay Üzerinden 8 Milyon Dolar Bağışlamış. Retrieved from: https://sozcu.com.tr/haber/baskentgaz-ensar-vakfi-na-kizilay-uzerinden-8-milyon-dolar-bagislamis-895888

Saurugger, S. (2007). Democratic ‘misfit’? Conceptions of civil society participation in France and the European Union. Political Studies, 55(2), 384-404.

Stiftung, B. (2020). Sustainable Governance Indicators. Retrieved from: https://www.sginetwork.org/2020/Turkey

Stefftek, J., Kissling C., & Nanz P. (2008). Civil Society Participation in European and Global Governance: A Cure for the Democratic Deficit? Palgrave Macmillan, NY: New York.

United Nations. (2019). Civil Society. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/sections/resources-different-audiences/civil-society/index.html

World Justice Project. (2020). The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index®. Retrieved from: http://worldjusticeproject.org/sites/default/files/documents/WJP-Global-ROLI-Spanish.pdf